Line and Meter… and Emojis? 🧐: The Poetics of Push Notifications

Published on August 29, 2018/Last edited on August 29, 2018/11 min read

Todd Grennan

Content Production Principal, Content Marketing at BrazeWe’ve all done it—looked down at the latest push notification to pop up on our phone, frown, squint, and think, “I wonder what a poet would make of this?”

No? Just me?

As Dana Gioia—California’s poet laureate and author of Interrogations at Noon and Can Poetry Matter?—says, "A poet might actually be a good idea to have in crafting and polishing messages. In the years I ran the NEA in Washington, I speculated that a well-written message might have disproportionate power in both the capital and the country. Indeed, it proved true."

In order to give marketing, growth, and engagement teams a fresh look at something they spend big chunks of their lives poring over, we’ve asked two poets to do a textual analysis of a curated selection of anonymized real-life push notifications. Our poets will dig into the ins-and-outs of how language is being used in push copy, touching on structure, content, rhythm, voice, and more, with a view toward decoding some of the hidden ways that these messages work (or don’t) when it comes to engaging their recipients.

Our first poet, Justin Boening, is the author of Not on the Last Day, But on the Very Last, which won the National Poetry Series. He teaches creative writing and edits Horsethief Books.

In your opinion, what poetic form—if any—do push notifications most closely resemble and why?

I hope I’m not breaking any hearts by saying this, but push notifications are like no poetic form I’m aware of. Sure, just like many compressed poetic forms, push notifications are defined by their necessary brevity. But whereas haiku, for example, has a number of more essential formal constraints—such as the way it employs image, or the manner in which it evokes a season, or the way it slows time to a crawl—push notifications are a language frontier largely yet to be defined.

What can mobile marketers learn from poetry, when it comes to the messages they send?

If what we mean by poetry is the most powerful, evocative, vitalizing, persuasive language, then it seems to me that mobile marketers stand to gain considerable insight from it. The great American transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson once said: “Every word was once a poem.” … If I were in marketing, I too would keep this truth in mind because, of course, the opposite of poetry—weak, uninteresting, exhausted, false language—is cliche. I hear a lot of cliche in my push notifications.

Our second poet, Laura Eve Engel, is the author of Things That Go, forthcoming from Octopus Books. She’s been awarded fellowships from the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, and more; her work can be found in Best American Poetry, Tin House, and elsewhere. She will happily write your app’s push notifications.

In your opinion, what poetic form—if any—do push notifications most closely resemble and why?

I’m going to go out on a limb and that push notifications could be (or should be!) more like a kind of spoken-word form, one that moves by urgency and presence. Spoken-word poets often play with presence in addition to language in the performance of their poems, and spoken-word poetry is a great place to study how poets—and push notifications—might consider the many demands on their audience’s attention, and earn the right to that attention through craft, honesty, and imagination.

What can mobile marketers learn from poetry, when it comes to the messages they send?

Just like in poetry, or in any form of communication, I think it’s important to keep in mind that our audience doesn’t owe us anything. That everything—whether it’s a poem or a push notification—needs to be its own reason for being. To a certain degree, all meaningful communication needs to argue for its existence by being compelling, by being urgent or impossible to ignore. By being true and unusual. The rest is just noise.

The Poetics of Push: 7 Messages and What They Summon Up

For this experiment, we asked our intrepid poets to engage with all manner of notifications: promotional campaigns and activity messaging, re-engagement push notifications, and messages nudging you to just update your app already. Let’s get into it!

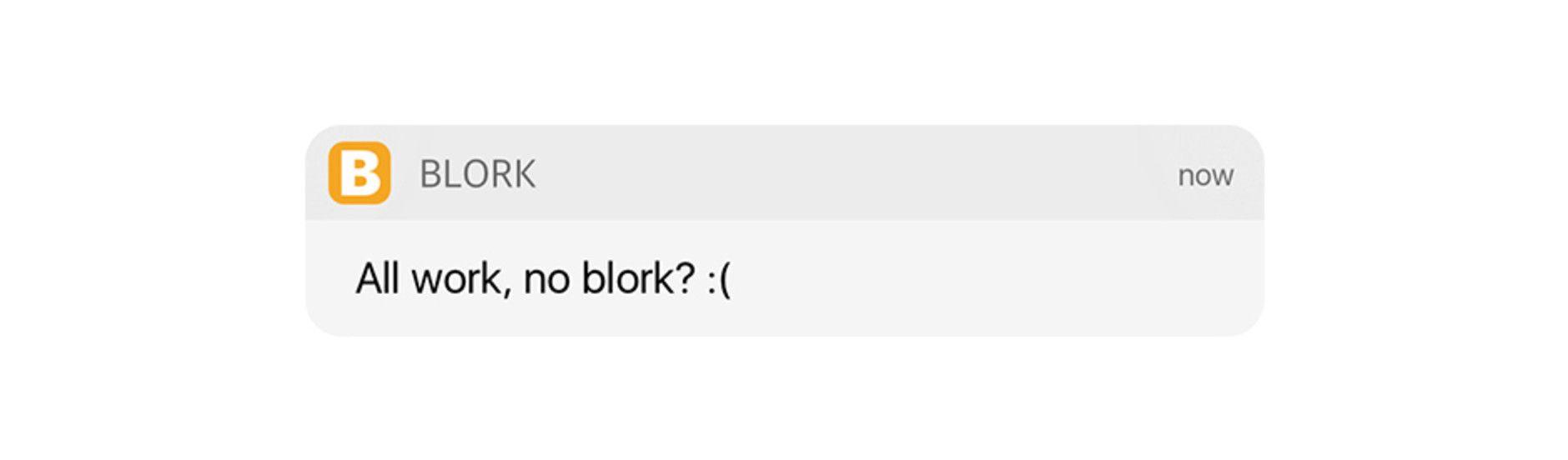

Justin

“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” We know this idiom. It’s been in circulation for hundreds of years … But post-1980, we remember this idiom first and foremost typed repeatedly by Jack Nicholson right before he goes axe-wieldingly homicidal on his wife and son. That we’re being asked to associate a push notification, which is to say, insentient brand language, with a minor-talent-burnout-alcoholic-killer is hilarious! And there’s little that’s more memorable than what’s funny.

Just as rich to me though is the gentle heightening of the rhythm here. Whereas the original phrase has ten syllables, this one has only four (plus two silent ones (kinda)). All of the unstressed syllables, the less important syllables—“and,” “makes,” and “a”—have been removed. What’s left is four stressed syllables, or two spondees (which is fancy-pants poet talk for a two syllable unit where each syllable receives an emphasis), and because those two spondees create a pattern, the ear quickly begins to create expectations. What it anticipates of course is more spondees, so that when we arrive at “no blork,” we expect to hear next, “dull boy.” In lieu of the words, however, we get an English to emoticon translation: “:(“. Which is again hilarious, because of course “dull boy” now means something close to paranormally possessed boy what with The Shining association, and paranormally possessed boy is so underexpressed by a sad face emoticon.

Bottom line, when language patterns itself, it creates expectations, and when expectations are created so too is the opportunity for subversion. And with subversion we get closer to art, which is to say something meaningful, surprising, and memorable, something you want to interact with.

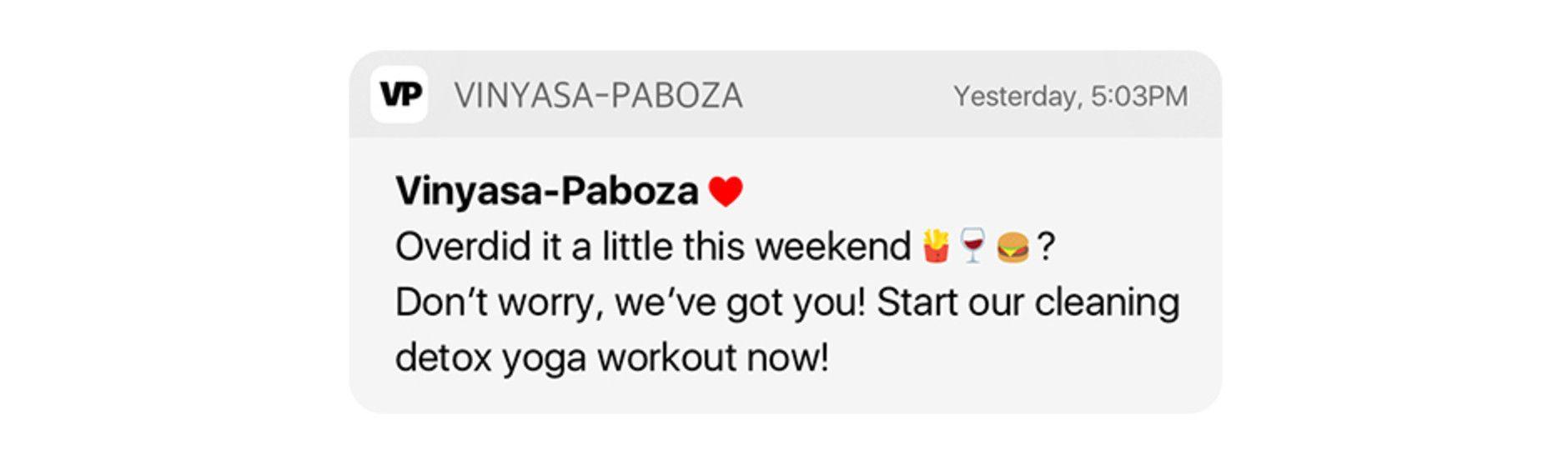

Laura Eve

This reminds me of the time a poet friend and I challenged each other to write poems in a passive-aggressive tone and then immediately realized how difficult it was to do, and what an excellent tonal exercise it was.

The juxtaposition of “overdid it a little this weekend” with the fries, wine and burger emojis communicates that this person didn’t overdo it in the typical sense—that is, instead of working too hard, they played too hard—but the fun (or perhaps nagginess) of this notification is in its indirectness. Being attuned to the subtleties of language to the extent that you can imply what you mean without actually stating it is an excellent tool to have in your language toolbelt.

Passive aggression as a tone is a gateway to other forms of linguistic subtlety, and it’s a fascinating laboratory for saying two things at once. It’s also one of the more infuriating—and, therefore, motivating—methods of communication. (I’m looking at you, Mom.) 😇

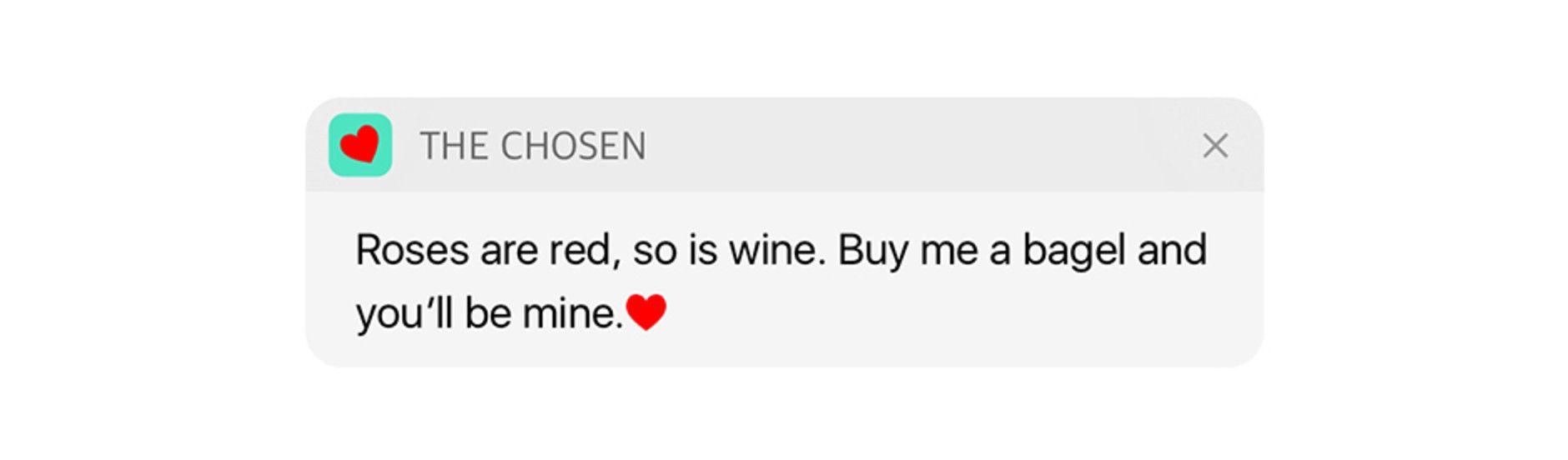

Justin

This is a classic rhyming quatrain, written in dimeter (meaning each line has two stresses). I’ll bold the stresses so you can follow along:

Roses are red,

so is wine.

Buy me a bagel

and you’ll be mine.

Most native English speakers, whether they’ve heard some variant of this nursery rhyme before or not, will see this notification and know it’s meant to be playful. It’s a little fleck of linguistic magic really, but much of its humor is tied up in the unstressed syllable at the end of the third line. It’s true. By virtue of English’s natural rhythms, we’re unlikely to hear a line end unstressed, and so our ear instinctively knows something is awry, off, funny. If you don’t believe me, check out Benny Hill’s iteration of this little verse, where he turns this odd effect up to eleven:

Roses are yellow

Violets are bluish

If it weren't for Christmas

We'd all be Jewish

As you can hear, when every line ends unstressed the language turns absurd! Something else that distinguishes this notification from many of the others I see is that it includes imaginable nouns: “wine” and “bagel.” This may seem like a pedantic distinction, but engaging the senses makes this language so much easier to hold onto.

Laura Eve

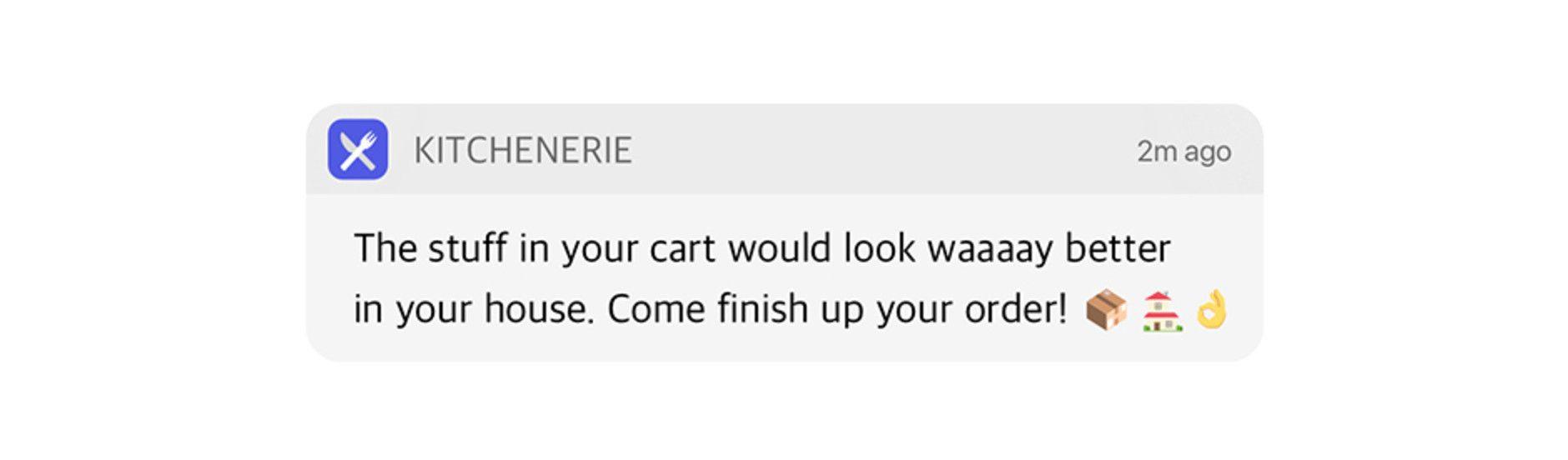

Never underestimate the power of an auxiliary verb like “would.” Technically the past tense of “will,” this word leaves room for a bit of uncertainty, which in turn signals a reader that imagination and fantasy are in play. “Would” conveys a future, but only conditionally—your home would look better if you make these few little interior decorating tweaks.

Poets use “would” in as many ways as it’s possible to use the word, but frequently it’s deployed in moments of profound imagination, as in this poem “It Would” by Alice Notley: “it would be that / but only if I knew how / again.” Here, the word gestures to the reader, suggesting we imagine a better, future home. The line between imagination and aspiration is a fine one, and activating either in your reader is an effective way to engage them.

Laura Eve

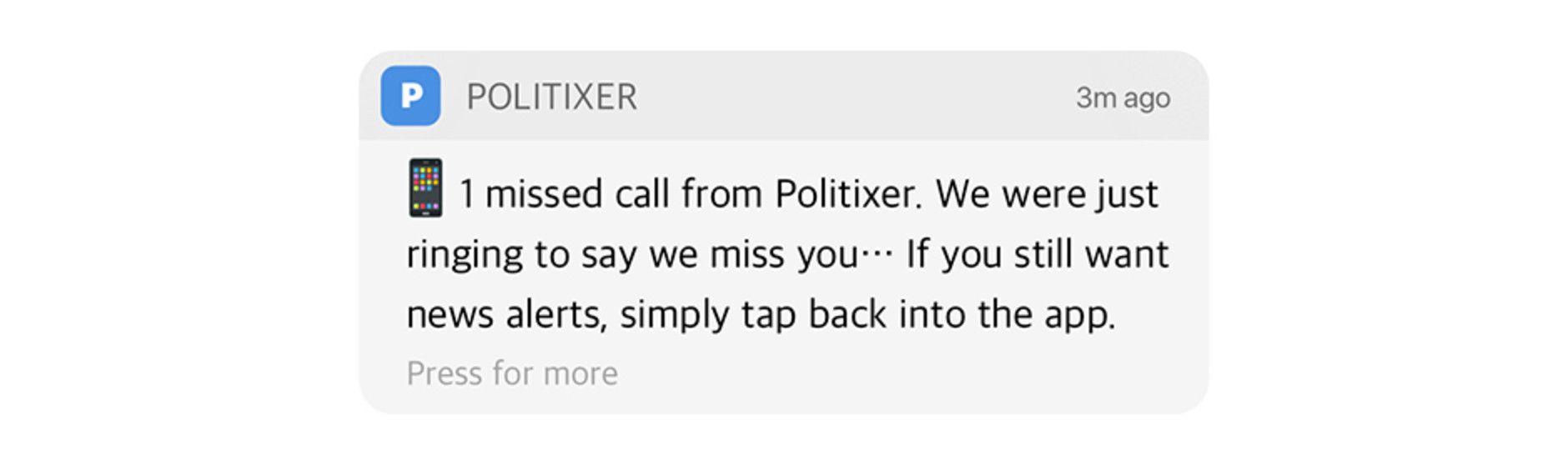

Apart from how everyone likes to be missed, there’s a nice, subtle moment here that’s worth pointing out: the phrase “simply tap back into the app” is resonant with a sonic technique called assonance. A $10 literary term for the repetition of vowel sounds in the middle of words, assonance can turn a simple call to action into a punchy, pleasing little phrase that’s full of hard “aaah” sounds. To coin another assonance-rich phrase: “Is that a smartphone in your pants? Because I’d like to tap that app.”

Justin

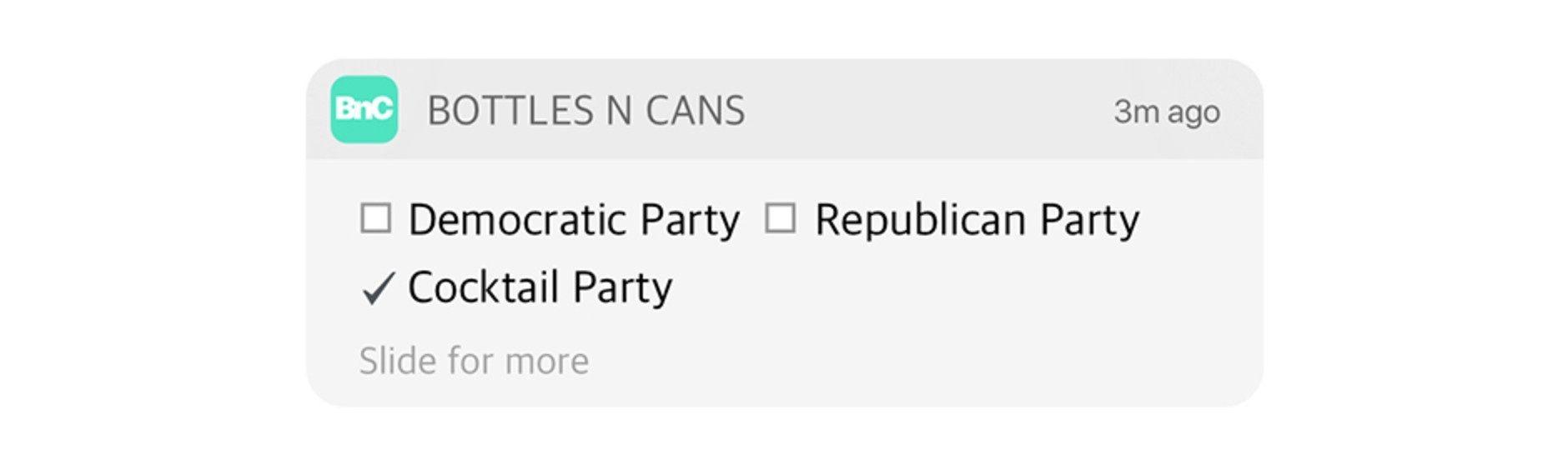

On its surface, this notification approximates the form of a voting ticket. Obviously. We get our first options, which are the choices we Americans would expect, and then those expectations are humorously subverted. The legerdemain is a play on the word party. And having the two uses of the word beside each other points to the sober humorlessness of politics, as opposed to the reckless freedom in a cocktail party. And freedom is what we want, right?

Beneath that surface, however, is a more subtle effect, and it’s caused by the root differences between words like democratic and republican and words like cocktail. The former two words are distinctly latinate, and native English speakers don’t need to be Latin scholars in order to hear that aspect of their nature. Latinate words tend to sound more intellectual, abstract, self-important—like politics. Cocktail, meanwhile, is Germanic, old norse, Scandinavian, and just as is the case with latinate sounds, even when we can’t hear those germanic roots, we can hear them. These words tend to sound more visceral, basic, essential, direct—like drunkenness.

The takeaway here, I think, is that English is so heavily influenced by other languages, that these dynamics are constantly at play and can be leveraged by an especially skilled or intuitive wordsmith as they are here.

Laura Eve

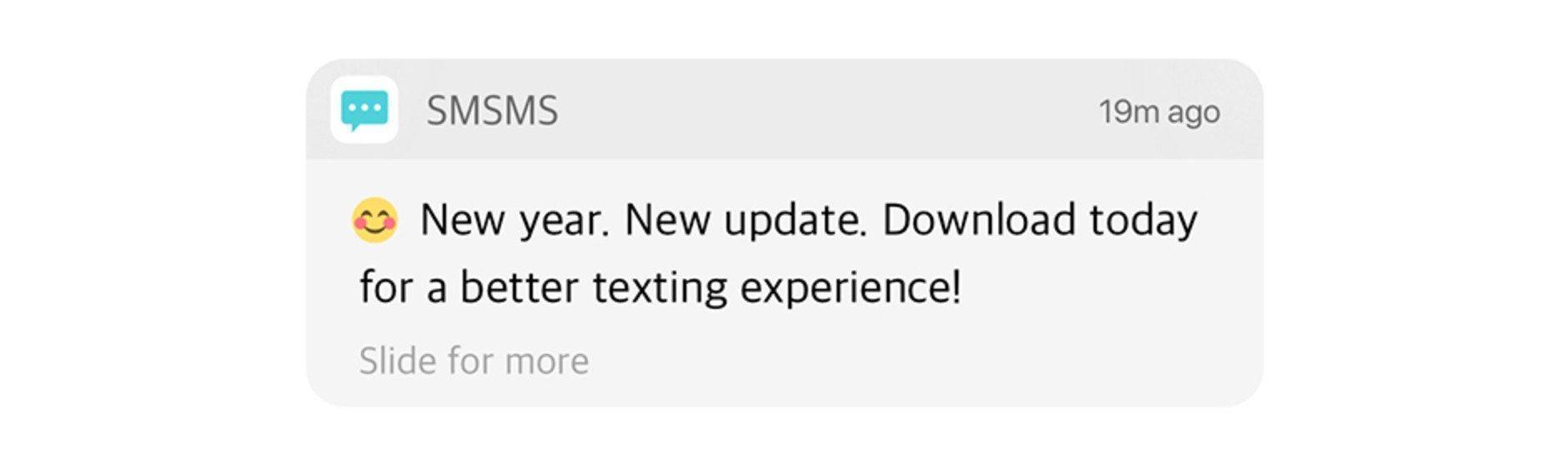

This construction—”New year. New update.”—uses one of my favorite rhetorical techniques of all time. Anaphora, or the repetition of the same word at the start of successive phrases or lines, is a common and super effective rhetorical strategy that is frequently put to use in poems, and is almost insufferably ubiquitous in political speechifying.

For history buffs, think Winston Churchill’s “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets…” Or, poetry-wise, think Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We real cool. We / left school. We // Lurk late. We / Strike straight.” (You can find the rest of the poem here. It’s short and urgent and has a lot to teach us about both anaphora and the power of brevity.)

While anaphora is plenty common among poets and politicians and push notifiers everywhere, it’s especially useful in these short forms because it creates a kind of sonic hook in the repetition of the same word twice (or more, if you’re game)—and who among us can resist a catchy hook? Who among us is not lulled by a gentle, rocking repetition? Who among us is immune the allure of anaphora?

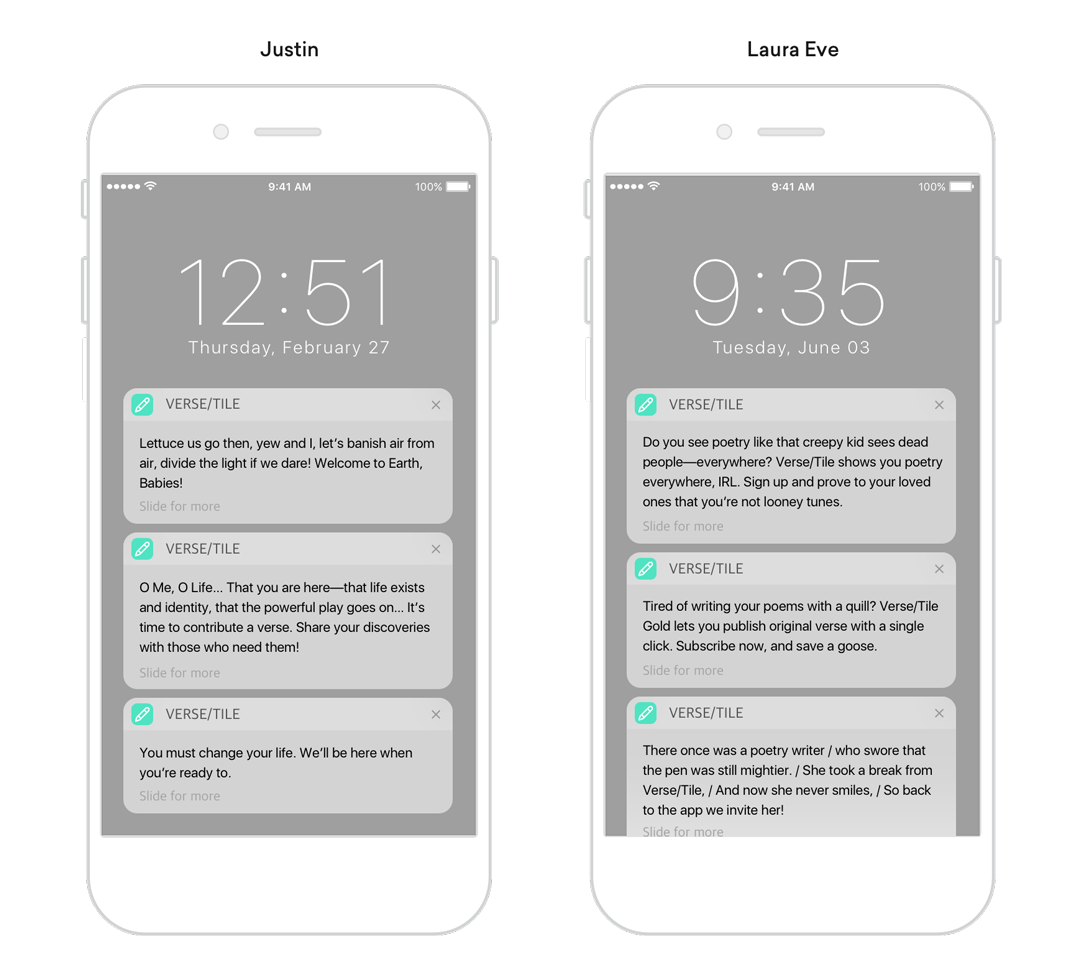

Role Reversal: Our Poets Try Their Hand at Push Notification Copy

After a long day analyzing and critiquing the language used in push copy, what better way for poets to unwind than by taking a crack at writing a few push notifications of their own?

We asked our poets to go a little outside their comfort zone and put together three pieces of push notification copy, including:

- A welcome message

- A promotional message

- And a winback message

The messages are designed to promote (highly fictional) Verse/Tile, an app that uses augmented reality (AR) to automatically translate found text in the real world—think street signs, restaurants menus, you name it—into poetry. Let’s see what they came up with:

Final Stanza

Okay, so push notifications may not be a type of poetry—yet!—but there’s a lot of insights to be gleaned from a close examination of the words they use and the way they work together. That said, there’s a lot more that can impact the success or failure of a given push notification. Timing. Segmentation. Personalization. Whether you chose to use an emoji or a image or a GIF. To dig deeper into push notifications, take a look at our exclusive guide to push.